Coastal Rowing Technique, Racing, and Navigation

Coastal rowing uses the same rowing stroke and principles as flat water sculling, but there are nuances to the technique, and special skills needed for racing.

Coastal Training

- Coastal training is similar to training for flat water racing with regard to basic fitness, though the coastal boats are considerably heavier.

- Do plenty of long distance rowing to build stamina, enhance basic fitness, and for injury prevention. If you are interested in coastal racing, consider adding in some erg workouts with the drag factor set approximately 30 higher than your typical setting. For example, women do coastal workouts at DF 140-150 and men at 160-170. The higher drag factor simulates the load of the heavy boat and water. Be sure to build a strong core and train your lats for the heavy load, too.

- Practice good rowing technique in coastal conditions (waves, currents, tides) and hone your navigation skills.

- Practice around-the-buoy turns for technique and speed.

Resources

- If you have never rowed, visit Learn to Row to get started.

- Learn the basics of Coastal Rowing from World Rowing and see a list of upcoming international events.

- Check out this PDF from World Rowing to learn about all aspects of Coastal Rowing.

- Advice on handling rough water: Rough Water Technique

Coastal Racing Rules

There is one main difference from the flat water head race rules:

A boat being overtaken does NOT need to yield to the overtaking boat. However, the boat being overtaken must maintain its course, and not engage in active “blocking” tactics.

- Contact among boats is allowed and often occurs going around buoys, as boats jostle for the most advantageous line. However, purposeful interference is forbidden. And as many champion coastal rowers know, “a clean course is a fast course.”

- So, while a rower must brave the crowd while making buoy turns, his or her fastest course usually will be one that does not make contact with other boats.

- Row clean! The early buoys in a race are the most congested.

Navigation Technique

Coastal rowing and racing often involves long distances across open water with strong currents, so navigation is key. Many rowers use GPS coordinates to guide their course, but steering off an electronic screen will often yield a path with numerous micro-adjustments and too much time spent with differential pressure, slowing the pace. A more holistic and faster strategy is to navigate using reckoning off the stern combined with anticipation of the current.

For example, if the course is generally to the north, but the current is to the west, then the rower must choose a point upstream, or so the bow is to the east of the destination. Look off the stern to find a point and hold it. Then the current will push the boat toward the desired destination. This is called “ferrying” or “crabbing” across the current, and uses the water to help get to the next point quickly.

Incorporate the direction of the current when planning buoy strategies. Currents can make buoy turns light and quick if the turn is with the current, or seemingly endless if the rower must turn against the flow. Worse yet, a strong current can push a boat away from a buoy before reaching it, which can disqualify a boat in a regatta or require the crew to re-take the buoy, losing time and distance.

In courses with strong currents, micro local variations can speed or stop a boat. The same water might yield a 6:00+ 500M split in one direction and a 1:40 split in the other. Or, traveling in the same direction, the tide or current might be markedly faster 10 meters to one side or the other as the water flows around obstacles or where the water’s depth changes dramatically.

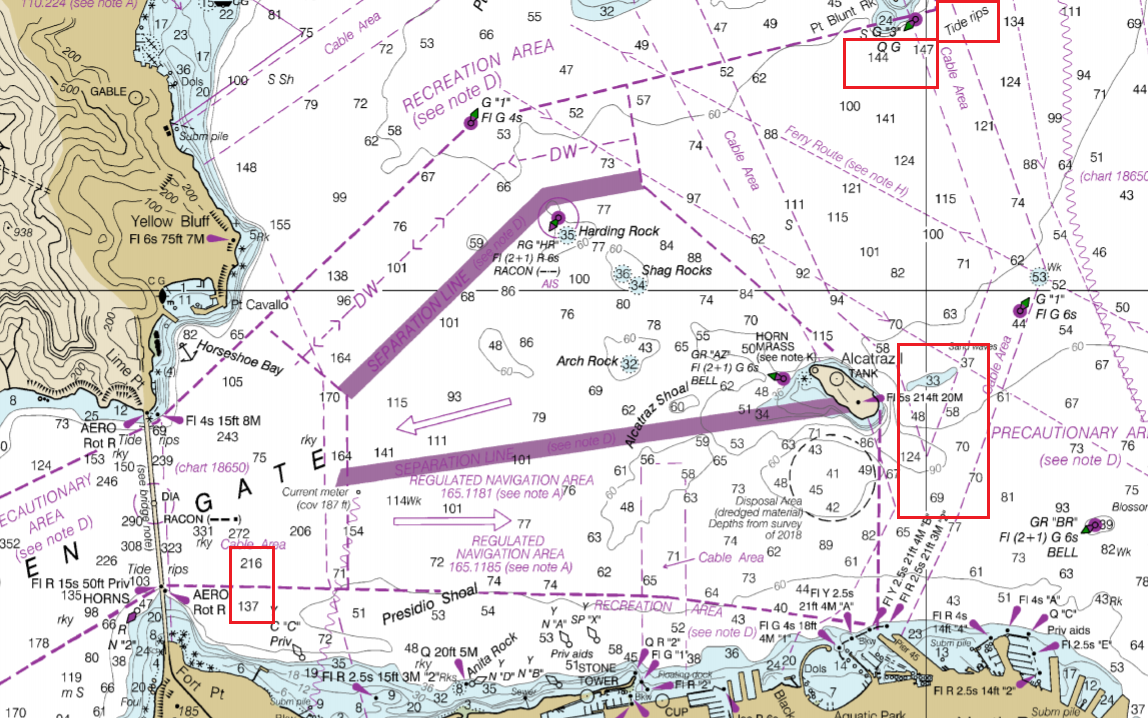

When traveling on a long stretch in the same direction where the currents are variable, move side to side and assess if the stream is helping more or less. Around obstacles, look at the current’s “shadow” to gauge where it is running faster. Batholithic maps show depth changes and can help rowers plan where to anticipate current changes. Current maps are also sometimes available (sailors use them along with other nautical charts) but in ocean waters, tides constantly change the local current.

Tides and currents in areas with complex coastlines rarely are strictly either ebbing or flooding. And the changes can be highly seasonal. In rainy months, freshwater flows can overpower tidal flows. In the San Francisco Bay, the “collision” of tides changing course meeting fresh water flows often yields a nearly unrowable chop just when the forecast is for slack tide. But those conditions often cover only a kilometer or so.

This chart shows some of the abrupt depth changes in the San Francisco Bay, highlighted in red.

At BIAC, the “Bermuda Triangle” of currents at the green channel marker number 13 just inside the wires is a great place to study currents and practice coastal rowing. The channel floor changes abruptly from 40 feet in the shipping lane to shallow waters. In addition, the currents in Westpoint and Corkscrew sloughs flow opposite of the main channel and intersect the channel perpendicularly, and offset from one another. Watch the water flows. Take our coastal boat out and try tight turns around the floating markers and enjoy the taste of crazy waters.